The Magic Circle: Gold Edition – An occasionally aimless, but always interesting, take on the game development process

****

Reviewed July 28, 2016 on Xbox One

Leave a comment on Giant Bomb

Disclosure: An Xbox One download code was provided by the publisher for this review

The Magic Circle is the tale of an unfinished game, trapped in development hell and straying from its original vision. Finally taking shape as a fantasy first-person RPG, its creative team are split: the series veteran is aiming for a lofty, nigh-unreachable vision, the title's director just wants something that'll sell in today's market, and the new intern/long time fan is determined to bring the series back to its roots by any means necessary. Though the gameplay occasionally stumbles, The Magic Circle's commentary on big-budget game development and its effect on the creative process never fails to be interesting.

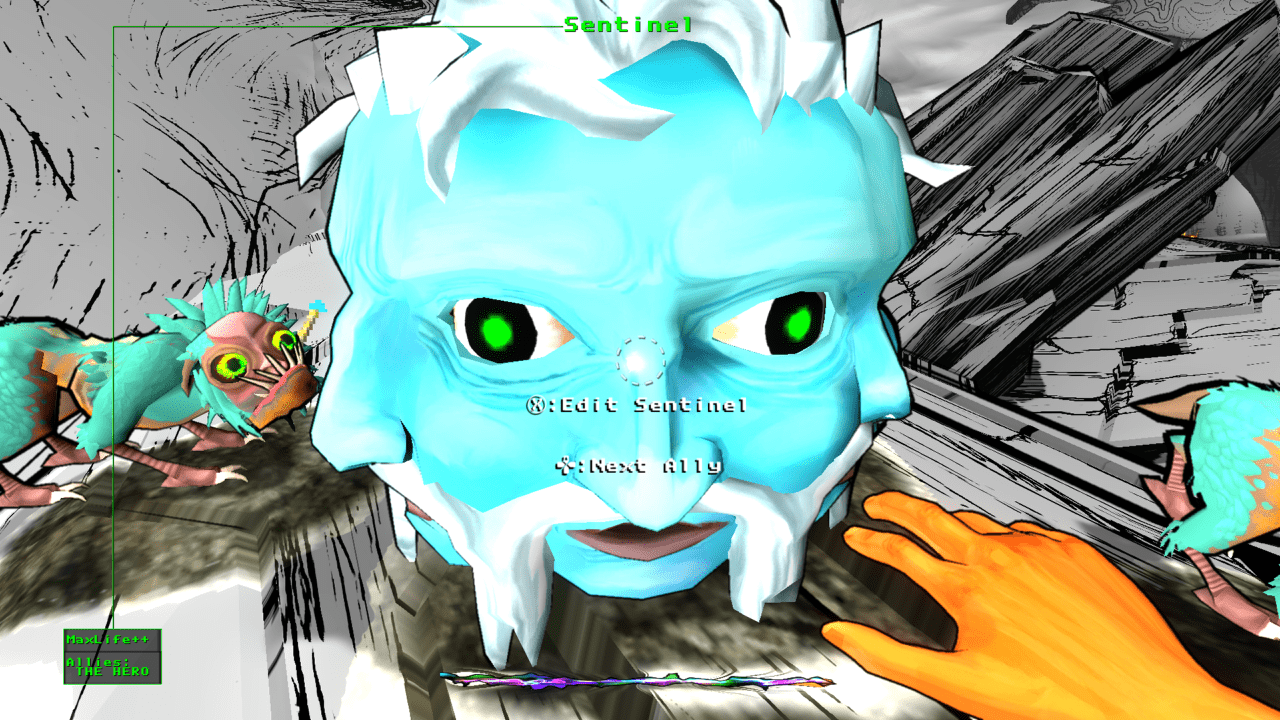

In The Magic Circle, the player takes on the role of a playtester, who is granted the ability to meddle with the programming of the work-in-progress game. Broadly speaking, this involves the restoration of previously deleted assets, and tampering with the behaviour of enemies. By trapping enemies, behaviours (such as attacks and special abilities) can be gathered, and these can be added to other enemies. This is easily performed - once a enemy is trapped, a list of fields can be edited by changing its value to one of the gathered behaviours. Towards the start of the game, I ran into a dog-like creature. Swapping "My enemies are Hero" for "My allies are Hero" granted me an ally who diligently did my bidding for the rest of the game.

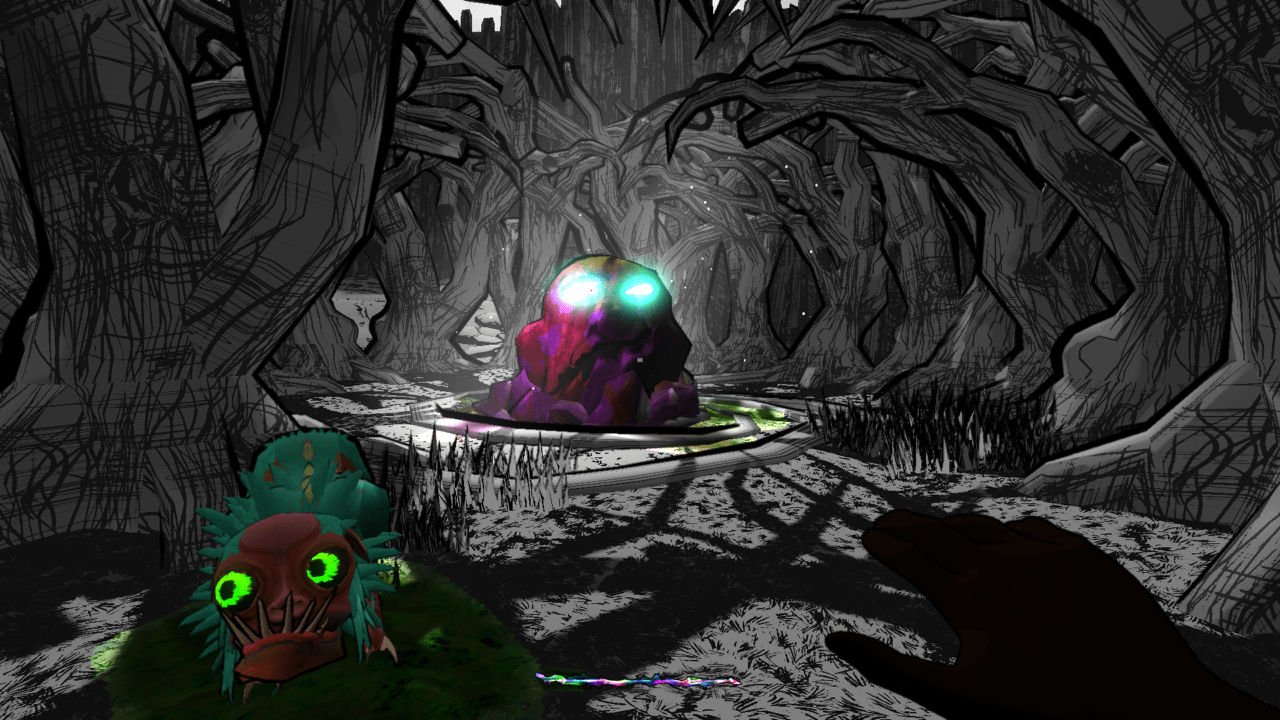

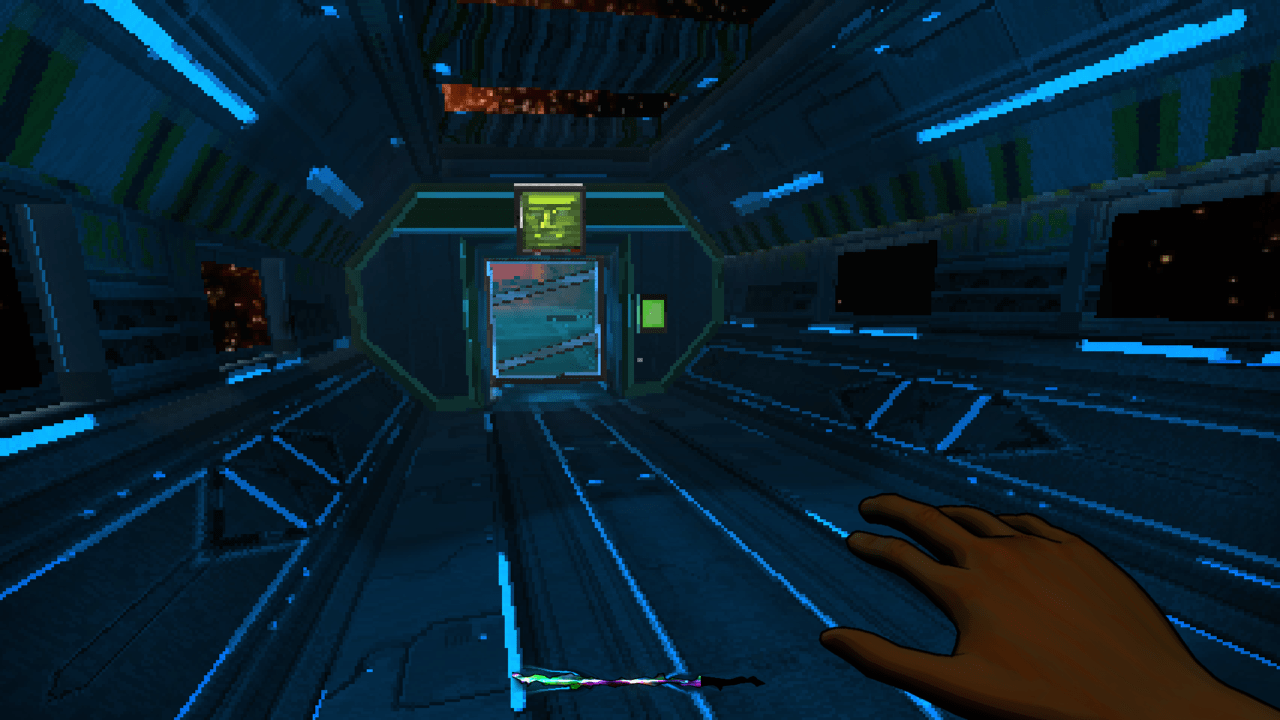

This experimentation with enemy behaviour forms the core of the game. From the stark, unfinished fantasy world, elements from the much older, but largely finished, sci-fi version of the game are covered. Enemy behaviours are modified to solve puzzles - for instance, applying "flight" to enemy gives a mobile platform that can be guided to new locations, or rocks may be given fire-resistance, allowing travel across otherwise impassable terrain.

This puzzle/experimentation gameplay largely works well, and it was satisfying to give former enemies new behaviours and see them do my bidding. This section of the game is fairly open-ended, and this occasionally meant it felt a little aimless - the main objective is known, but I was largely left to my own devices to explore the unfinished game and find the elements I needed to achieve that goal. The rest of the puzzles in the area were largely incidental, and could potentially be ignored if I found an overall solution with what I had already gathered.

This openness is not a problem per se, but the slow movement speed and relatively limited fast travel lead to a lot of downtime. The unfinished nature of the world also adds to this - the black-and-white, limited visual style makes sense from a narrative standpoint, but it quickly becomes uninteresting. The older, sci-fi sections of the game resemble something such as Doom 3D. It's a neat style, but becomes repetitive soon after being introduced.

Throughout this section, the game's development team are represented by giant floating eyeballs, and they are working towards a fast-approaching 'E4' demo (or more accurately they are bickering about it, but not getting much done). The characters, plus an "old pro" who granted the editing ability, form the backbone of the narrative, and deliver cutting remarks on the nature of crowd funding, entitled fans, the pitfalls of a large studio, and design clichés. It is especially interesting that the game is described by the characters as an unfinished mess, but it took considerable skill on the part of the real-world designers to create a world that superficially seems broken, yet can support the player messing with its systems.

Some of these narrative segments drag on, particularly during the E4 demo, and I often found my self staring into a disembodied eyeball waiting for the scene to finish. There is tremendous irony in the fact that overly long story sections are present in a game where one character frequently mentions that the audience doesn't care about the story; I almost wonder if it was deliberate. Fortunately, the story is well-written, meaning that even these extended sequences provided an interesting, and usually amusing, insight in the problems of game development. A lengthy rant by the series veteran on the impossible expectations of the industry and fans was a particular highlight.

Around half-way through the game, I was initially disappointed to discover that the gameplay takes a sudden turn, and the free-form editing tools are largely removed. Just as I felt comfortable with the tools, the game rapidly moved away from these, and began to take on a more story-heavy form. There is an clever, and unexpected, twist on the idea at the end of the game, but The Magic Circle very much feels like a game of two halves: the first half is free-formed with a variety of tools, the second is considerably more linear with fewer options for the player.

All in all, The Magic Circle is a largely successful commentary on big-budget game development and the factors that conspire against making a good game: unattainable perfection, unrealistic fan expectations, business realities to name a few. Though it is not a perfect game by any means, arguable the take-home message of The Magic Circle is that it never could be. The mid-game spilt of free-form creativity versus a more linear guided narrative perhaps means that it'll be disappointing to players looking for either one, but The Magic Circle balances the two nicely, reflecting the game's message of how difficult it can be to build a balanced game. Despite a few frustrations with the gameplay, I greatly enjoyed my time with The Magic Circle.